Les Amis d'Escoffier Society Boston, LTD.

Member Login

Dedicated to Auguste Escoffier the King of Chefs and to the enjoyment of fine dining in the style of which Escoffier's cuisine encompised with other food and wine enthuiasts.

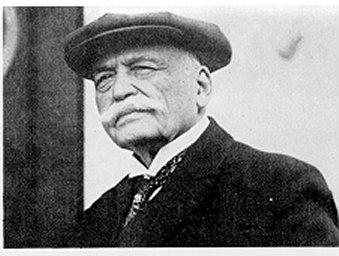

Chef Escoffier

Escoffier has been hailed as the king of chefs and the chef of kings.

He was the undisputed culinary leader in the thirty years before World

War I, when crowned heads, led by the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII)

toured the fashionable resorts of Europe accompanied by the beauties of

the day, and when the Wagons-Lits company ran a regular service from St.

Petersburg to Cannes. Escoffier was also the chef of chefs, defining for

his profession the art of modern French cooking, reducing to essentials

the elaborate structure of haute cuisine inherited from Careme.

London, Paris, Cannes, Monte Carlo, Nice, Lucerne---at one time or

another between 1880 and the war, Escoffier headed the finest kitchens

in them all. The situation was very different from the days of Careme;

restaurants, from being a generally inferior alternative to dining at

home, had taken the lead. No longer did the great chefs work in private

houses for individual masters; instead the masters came to them in their

restaurants and hotels. At the Cafe Anglais in Paris, headed by chef

Duglere of sole Duglere fame, "one supped until midnight, the baccarat

lasted until dawn and the Russian princes broke the house glasses with

blows from the bottles of Champagne."

The

great hotelier Cesar Ritz was the perfect partner for Escoffier. Their

association lasted almost forty years and extended to five of the

greatest hotels in Europe.

The

great hotelier Cesar Ritz was the perfect partner for Escoffier. Their

association lasted almost forty years and extended to five of the

greatest hotels in Europe.

Escoffier, king of the kitchens of the time, once recalled the

greatest mishap of his career-the day an inexperienced waiter tipped a

dish of peas down a lady's dress. Losing his nerve completely and

stammering in broken English, the poor man began frantically to retrieve

the peas one by one, until he was knocked to the poor by her outraged

husband.

The achievements of Escoffier are hard to separate from those of Cesar

Ritz, the great hotelier whom Escoffier met in 1880 at a providential

moment in his career. Escoffier was thirty-four, with a thorough

training behind him, but at the time of this meeting there seems to have

been little hint of his special gifts. After a six-year apprenticeship

at his uncle's restaurant in Nice (near Escoffier's home village of

Villeneuve-Loubet), Escoffier had gone to Paris when he was nineteen,

spending the next five years at the fashionable Le Petit Moulin. Later

he admitted how hard he found the work; a sensitive man, the conditions

of a busy kitchen with its incessant din and vulgar behavior were hard

to bear and being small, Escoffier was forced to wear platform shoes to

avoid suffocation by the burning heat of the stovetops. At the time of

the siege of Paris in 1870 (famous for its culinary curiosities

population began to deplete the zoo), he was drafted as chef de cuisine

at the headquarters of Rhine army in Metz. Metz too was put under siege.

"Horsemeat," Escoffier later remarked, "is delicious when you are in the

condition to appreciate it...and as to rat meat, it approaches the

delicacy the taste of roast pig.

Soon after this war ended Escoffier returned to Paris where he spent six

years as head chef of Le Petit Moulin, followed by posts in several top

restaurants. Then, at the height of the winter season at the Grand Hotel

in Monte Carlo, Cesar Ritz lost his chef Giroix to the rival Hotel de

Paris. Escoffier was called in, and so began the great partnership. In

the next six years Escoffier divided his time between Monte Carlo and

Ritz's Grand National Hotel in Lucerne, resorts frequented by such

celebrities as the Emperor of Austria and the Prince of Wales, for whom

Escoffier created his poularde Derby. Ritz was past master at attracting

such a glittering clientele; his unerring chic was combined with a gift

for making each guest personally welcome, to which Escoffier added the

crowning touch with his superb cuisine.

Escoffier cut down on the cumbersome garnishes that had survived from

the eighteenth century, substituting instead a few simply-cooked

vegetables and a sprinkling of parsley, insisting that all must be

edible. He gave up the ornamental hatelets (skewers) impaled with

truffles, cockscombs, and crayfish, and the elaborate socles on which

food had been mounted so as to be more impressively displayed. Food, he

believed, should look like food. He had an equal abhorrence of a

profusion of flavors and aimed instead to achieve the perfect balance of

a few superb ingredients. Typical was his sole Alice, where sole,

poached in wine, is heated in a chafing dish in a sauce flavored with

shallots and thyme, to which oysters are added at the last moment.

Escoffier was quick to point out that such simplification marked a

development, not a decline, in the art of cooking: "What already existed

in the time of Careme, which still exists in our time, and which will

continue as long as cooking itself," he declared, "is the fonds

[foundation] of that cooking; because it is simplified on the surface,

it does not lose its value; on the contrary. Tastes are constantly being

refined and cooking is refined to satisfy them."

In 1889 the Ritz-Escoffier team took over the Savoy Hotel in London. By

now their reputation was unrivaled, and they were followed at once by

the Rothschilds, the Vanderbilts, the Morgans, the Crespis, and the rest

of the beau monde. Escoffier was kept busy with his new dishes-coupe

Yvette, poularde Adelina Patti, consomm favori de Sarah Bernhardt, and

salade Tosca are just a few of the hundreds of creations of his fertile

imagination. Ritz, with his inimitable style, had persuaded ladies to

dine in public for the first time; professional beauties like Lily

Langtry were often to be seen at the Savoy, and Nellie Melba lived there

whenever she was singing across the way at Covent Garden. It was after

her performance in Lohengrin that Escoffier served the first version of

peches Melba, poached peaches on a bed of vanilla ice cream set in a

swan of ice, recalling the swan in the Wagnerian opera. (Not for several

years did Escoffier add the crowning touch of raspberry sauce).

When Ritz opened his hotel in the Place Vendome in 1896, the story was

the same, and all Paris flocked to sample Escoffier's cuisine. Three

years later he was on the move again, back to London and Ritz's new

Carlton Hotel. Here at last he found time to assemble his recipes and

ideas on cooking, published as Le Guide culinaire in 1902.

Le Guide culinaire is an astounding compendium of classic recipes and

garnishes-over 5,000 in all, and Escoffier acknowledges the help of

several other top chefs. Starting with the founs-the basic sauces,

stocks, and pastries-Escoffier builds them like bricks into the great

dishes for which he and the chefs before him were so famous. "A tool

rather than a book" was his stated aim, and behind its somewhat

forbidding facade of technicality lie forty years of practical

experience in making almost every dish. What it is not, is a guide for

the private kitchen, and even a layman who can follow the recipes would

still be hard pressed to reproduce them at home. For example, the recipe

for one of Escoffier's specialities, tournedos Rossini, in the space of

five lines uses two technical terms (sauter and dglacer), two basic

preparations (meat-glaze and demi-glace sauce) which take hours of

advance cooking and which themselves demand other basic preparations,

and an ingredient (fresh foie gras) which is a rarity even in Paris. To

the professional chef, however, who knows cooking terms intimately and

has all the basic sauces ready at hand, Le Guide culinaire is the

perfect quick guide to thousands of recipes-it is indeed the "constant

companion" that Escoffier hoped it would become.

Escoffier was not without his critics. "It would be difficult to serve

these supremes in the way they were created," remarked a cookbook called

La grande cuisine illustre, referring to an Escoffier dish supremes de

volailles Otro. "Their only originality, hardly a recommendation, was

to be placed on croutons cut from truffles of which the smallest must

have weighed a pound after peeling." The writers were two young chefs,

Prosper Montagne and Prosper Salles, both trained under Giroix,

Escoffier's rival in Monte Carlo. Their book shows even more clearly

than Le Guide culinaire (which appeared two years later) how far cooking

had developed from the fulsome pieces montees of mid-century, but it was

a less comprehensive work than Escoffier's and never earned the same

fame for its authors. It was more than thirty-five years before Prosper

Montagne proved himself Escoffier's equal in influence and prestige as

author of Larousse gastronomique, the outstanding encyclopedia of

cookery to which Escoffier contributed a generous introduction just

before his death.

Escoffier's greatest innovations were in menu planning, which had

already begun to change shortly after Car�me's death in 1833. For

hundreds of years, dinners had been served in the style called a la

francaise, with a large number of different dishes set out on the table

at once. The dishes might be changed twice or even three times to make

three or four courses. The basic idea was to make an impressive show of

luxury, with as great a variety of dishes as possible (a principle

dating from medieval banquets). Service d la russe, which gradually

replaced service a la francaise, is the practice we know today of

serving dishes consecutively rather than simultaneously. It has two

great advantages: food is served at once while at its best, and wastage

is reduced because quantities can be estimated better. Car�me had come

across service a la russe during his time in Russia and it did not suit

his love of show. "This manner of service is certainly beneficial to

good cooking," he admitted, "but our service in France is much more

elegant and of a far grander and more sumptuous style."

For this reason service a la russe was slow to spread and it was not

until 1856, when Urbain Dubois, who had cooked for twenty years in

Russia, produced his massive La Cuisine classique with Emile Bernard

(both "men of genius" in Escoffier's eyes) that the method caught on. By

the 1870s, when Escoffier appeared on the scene, serviced la russe was

universal, enabling him to drastically reduce the number of dishes in

his menus. In Le Livre des menus, published in 1912, he outlines the

principles that should underlie a well-planned meal: it should be

appropriate to the occasion and to the guests; the season should always

be borne in mind; if time is limited, the menu should be as well, and in

any case a superfluity of courses should be avoided.

A typical winter dinner served at the Carlton Hotel consisted of: blini and caviar; consomme; sole in white wine sauce; partridge and noodles with foie gras; lamb noisettes with artichoke hearts and peas; champagne sherbet (all such menus were broken up by a tart wine or fruit sherbet to refresh the palate); turkey with truffles; endive and asparagus salad; and various desserts. Even allowing for smaller helpings, such a repast is lavish by our standards, but nonetheless it called for but a fraction of the dishes that Careme would have served for a comparable meal a la francaise.

Grey-haired and gentle of manner---according to Madame Ritz he

"looked like a man of letters"---Escoffier would leave the kitchen

rather than lose his temper with an erring subordinate. In this he was

very different from the traditional loud mouthed chef. At the beginning

of his career, the profession had not been highly regarded, and with his

own unhappy apprenticeship in mind, Escoffier was determined to improve

it. He forbade the swearing and general brutality that had been the

rule, insisting that a well-run kitchen should be calm. He himself never

raised his voice and, symbolically, he changed the name of the aboyeur

who barked out orders to announceur. About the appalling heat he could

do little, but he saw to it that a caldron of barley water was always

available for quenching thirst, thus cutting down on the consumption of

beer and wine, the cook's habitual failing.

Even more important was Escoffier's revision of kitchen organization.

Since medieval times, kitchen staff had been divided into sections, each

of which was more or less independent. This meant that general

preparations like sauces or pastry might be made several times by

different sections-a wasteful duplication that also made quality hard to

control. Escoffier reorganized his kitchens into five main sections,

called parties, each dependent on the others. The patissier produced the

pastry for every partie, the garde-manger supervised the cold dishes and

supplies for the whole kitchen, while hot dishes came either from the

entremettier (in charge of soups, vegetables, and desserts), or from the

rotisseur (roasts and broiled and fried dishes). Second in command under

Escoffier, as befitted his importance, was the saucier. When a dish was

ordered, not only could it be rapidly assembled by the appropriate

parties, but Escoffier could more easily keep an eye on the finished

result. A similar system is still followed in large kitchens today.

Though generally regarded as a great exponent of the grande cuisine

found in restaurants, Escoffier was equally at ease in a private

kitchen. His Ma cuisine, published in 1934, is an admirable survey of

the cuisine bourgeoise that is so popular today-the poulet saute

bourguignonne, brandade de morue, and pat de veau et de jambon that are

the backbone of French family cooking. The book is as comprehensive as

Le Guide culinaire and infinitely more usable, with fewer

cross-references and more explanation. In Escoffier's own words, "It is

not a simple aide-memoire, but truly a cookbook with recipes that are

practical and as clear as possible." Nonetheless Escoffier takes for

granted considerable cooking knowledge he gives some quantities but not

in a systematic manner. He makes no mention of oven heats, cooking

times, or number of servings.

Escoffier remained at the Ritz Carlton until the end of World War I,

retiring to Monte Carlo to join his wife when he was seventy-three. He

had spared little time for his family (he had three children) but he

could look back on six decades of total commitment to cooking. He is

remembered as the outstanding chef of the last hundred years and his

Guide Culinaire is still the primary book of reference for his

profession. It is to Escoffier that we owe the familiar shape of modern

menus which, though reduced since his time, still follow the same

logical pattern, and it is he who created many of our favorite dishes.

Above all, it is Escoffier who finally put an end to the medieval

principle of luxuriant display; after 500 years, quantity had at last

surrendered to quality, and gluttony to gourmandize.

More

about Escoffier---Chef John Vyhnanek ![]()

A Peach Melba Story--- aftouch_cuisine.com

The Savoy in London--- 4Hoteliers ~ 2001-2009

Escoffier Timeline---Newly Updated Thanks to Chef Talleyrand of New

Zealand ![]()

Old

British Institutions---Lieutenant-Colonel Newman Davis,

The London Times, Monday, June 8, 1914 ![]()

Boston Cooking School 1909, In Escoffier's Kitchen

Culinary Terms used in French Cuisine